The Color of Wine

An in-depth look into the full-bodied spectrum of colorful vinos across the globe

Drinking wine is a sensory experience that engages not just the palate but also the eyes. Before the glass even touches your lips, the first interaction with a wine is through its color. This visual cue can reveal important clues about the wine’s character, including its grape variety, age, body and winemaking techniques. As with all things nuanced, the color of wine is not just about aesthetic appeal but also about understanding its story and heritage.

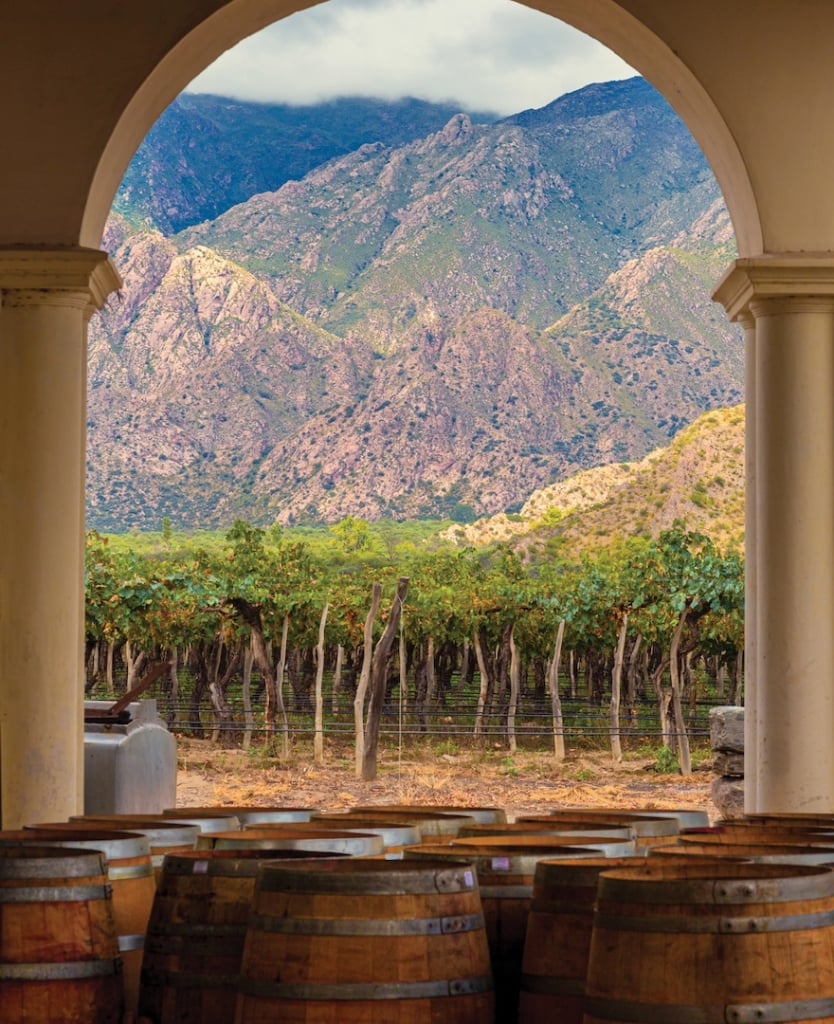

Barrels of wine stored in the Buena Vista Winery.

“They say we eat with our eyes, but in truth, we drink with our eyes as well,” says Jean-Charles Boisset, the charismatic French proprietor of Boisset Collection, one of the world’s most respected family-owned wine firms. Whether it’s the iconic Red Room at Raymond Vineyards in the heart of Napa Valley or the stained glass accents that give the barrel cellar at Jean-Claude Boisset in Burgundy’s Côte de Nuits the air of a cathedral to wine, few vintners bring as much visual flair to their properties as the Boisset Collection. This kind of visual storytelling begins the moment we set our sights on a glass of wine, as its color reflects the winemaker’s artistry and the wine’s origin.

Wine colors can vary widely, from the deepest purples and bright reds to golden yellows and pale greens. Historically, wine choices were largely confined to simple red or white categories. However, today’s wine enthusiasts encounter a broader spectrum that includes not just reds and whites, but also pinks and oranges, each telling a unique tale about the wine’s journey from vineyard to bottle.

ONLY SKIN DEEP

Wine fermenting in oak barrels in the Cafayate Valley

Understanding wine color starts with the grapes—generally, white wines come from green or yellow grapes, while red wines are made from dark-skinned grapes. The key to this transformation lies in the winemaking process, particularly the role of grape skins.

The skin of the grape contains pigments that can greatly influence the color of the wine. For example, red wines get their color from extended contact with grape skins during fermentation—a process known as maceration. “The longer the skins are in contact with the juice, the deeper and more intense the color becomes,” explains Rajat Parr, an internationally renowned winemaker and sommelier, and Director of Farming and Winemaking at Stolo Vineyards in Cambria, California.

Conversely, white wines are usually produced by quickly separating the juice from the skins and seeds, preserving their lighter color. But exceptions exist, such as Champagne, which is often made from a blend of both white and red grape varieties but still appears white because the skins are removed early in the process. A prime example of this is Dom Pérignon, one of the most iconic Champagne houses in the world. Known for its elegant complexity, Dom Pérignon achieves its signature style by blending black and white grapes, balancing the depth of red grapes with the brightness of white, all while maintaining its golden hue.

Rosé wines, straddling the line between red and white, achieve their pink color through a brief period of skin contact, far shorter than that of red wines. This delicate process results in a range of pink shades, from pale blush to vibrant salmon. “A rosé gets its pinkish hue from limited skin contact—just a few hours compared to weeks or months for red wines,” notes Patrick Cappiello, winemaker and proprietor of Monte Rio Cellars in Sonoma County, California.

Pierreux Vineyard in France

COLORFUL CLIMATES

Color can also provide clues about a wine’s age, as the color of a wine can vary over time. White wines typically gain color as they age, becoming more golden with notes of brass. A young chardonnay might be a vibrant yellow or gold but turn darker as it ages. On the other hand, age has the opposite effect on red wines. Reds tend to lose color as they age. After several years, a rich cabernet sauvignon might look orange or brick in color. Older reds have less color because of the exposure to oxygen that removes color from the wine. But have no fear, there are ways to stabilize color in wines. Storing red wine in oak is one of the most popular ways to keep the color in wine.

Another determining factor in the color of wine is climate. Warmer climates tend to produce darker-colored wines such as grenache and colder climates produce lighter-colored wines like a riesling.

“One of the biggest impacts on the thickness of skins can be the environment the grapes grow in,” says Jonathan Eichholz, a Master Sommelier based in New York City. “A few ways you get very thick skin on grapes are wind, elevation and exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays. For example, malbec is a super thick color with a lot of pigment because it has a high elevation, wind and a lot of UV exposure. Wind will make thicker skins. That’s why pinot noirs in Oregon have slightly deeper colors because of extra wind.”

Climate also has a direct impact on the pH levels in a wine, which measures its level of acidity. The lower the pH, the higher the acid in the wine, and the less color it’s going to have. Elevated pH levels correlate with darker colors and lower acidity levels. Colder climates, where grapes hang on the vine for longer periods, produce higher pH levels in grapes than warmer climates.

While the color of wine is often a natural byproduct of the varietal and the climate, winemakers can and do manipulate the color of their wines to a desired effect, particularly in reds, through the process of maceration.

Sea Island Pairings

Sea Island has an impressive, award-winning wine collection with more than 1,000 labels from all over the world, including vintages that date back to the 1920s. When Ryan McLoughlin, Head Sommelier at Sea Island, looks for the perfect pairing of food and wine, he searches for a wine that will enhance a diner’s meal.

Sea Island has an impressive, award-winning wine collection with more than 1,000 labels from all over the world, including vintages that date back to the 1920s. When Ryan McLoughlin, Head Sommelier at Sea Island, looks for the perfect pairing of food and wine, he searches for a wine that will enhance a diner’s meal.

Dark colored red wines, which are fuller in body and texture, pair well with fine cuts of meat. If someone orders the Frenched Bone-in Ribeye from Colt & Alison, “I’d look for a full-bodied wine with elevated tannins to pair with it,” says McLoughlin. “A full-bodied wine such as a cabernet sauvignon from California or a Bordeaux from France will cut through the fat of the ribeye, and cleanse the palate upon every sip, so you’ll be prepared for your next bite.”

Georgian Rooms wine pairings curated by Head Sommelier at Sea Island, Ryan McLoughlin.

When it comes to white wines, McLoughlin recommends pairing a rich chardonnay with halibut or a more substantial seafood dish like lobster. For the Snapper Meunière accompanied by the fava bean-black truffle risotto served in Georgian Rooms, an exceptional choice would be a white Burgundy. This wine offers a delicate balance, with enough subtlety to complement the snapper without overshadowing it. “I look for wines with great acidity to cut through the creaminess of that truffle risotto,” McLoughlin notes, highlighting the harmonious interplay between the wine’s vibrant citrus notes and the dish’s luxurious textures.

Orange wines are great since they offer that tannin structure that you would not get traditionally with white wine. “Because of their structure, orange wines pair well with richer and bolder flavors,” McLoughlin says. “I prefer to pair them with spicy and robust flavors such as curry or soy-based dishes.”

Rosé wines are wonderfully versatile due to their refreshing acidity and light-to-medium body. “These wines are excellent with dishes that have pronounced and fresh flavors,” says McLoughlin. “I love pairing them with Mediterranean cuisine, such as grilled vegetables or the branzino served in Tavola. Their crispness complements seafood dishes beautifully.”

ORANGE IS THE NEW WHITE

Maceration is how reds get their color, but what happens when you macerate a white grape? You get orange wine, which is one of the newest trends for both wine drinkers and producers.”

Maceration is how reds get their color, but what happens when you macerate a white grape? You get orange wine, which is one of the newest trends for both wine drinkers and producers.”

“Almost any white wine that’s fermented on the skin will produce an orange wine, and the longer you leave it on the skin, the more dense the color tends to get,” says Patrick Cappiello, winemaker and proprietor of Monte Rio Cellars in Sonoma County, California.

While orange wine is a relatively new trend, it has actually been around for a long time. Orange wine is what wine looked like thousands of years ago. It dates back to the origins of winemaking in the country of Georgia around 6000 BC, and is the oldest style of winemaking. Ancient wine producers would let the juice sit with the skins, seeds and stems in a clay vessel until it gained color and texture.

This timeless, ancient process has recently taken on a new life. Demand for orange wines has exploded in recent years as consumers have become more knowledgeable and adventurous. As a winemaker, Cappiello was hesitant at first to produce orange wine because he wasn’t sure if it was a fad, and chasing after trends as a winemaker can be dangerous. Once production catches up to the trend, it may be over. But now his confidence has grown in their enduring popularity, producing two different kinds of orange wine, one of which ranks as his third best-selling wine. “I don’t think it’s a trend anymore,” he says. “It’s slowly becoming a standard.”

Today, most restaurants that have a robust wine program will have an orange wine by the glass. It’s definitely an important category of wine with a rich history and an exciting future. Mike Veseth, editor of The Wine Economist, notes that the recent popularity of orange wine is a revival of ancient practices. “This style of winemaking is a return to roots, offering a complex and intriguing alternative for modern palates.”

Understanding the color of wine goes beyond simple aesthetics. It encompasses the grape varietals, climate and winemaking techniques that contribute to the final product. As the wine industry continues to innovate, new trends like orange wine are likely to redefine the spectrum, offering wine enthusiasts a richer and more colorful experience.